You'll be surprised

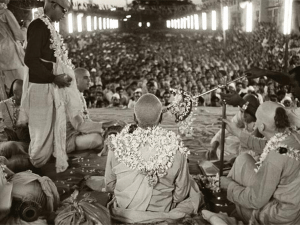

Visakha Devi Dasi: The devotees could not have picked a better location for their festival than Cross Maidan, a huge, easily accessible area in the center of Bombay enclosed for the occasion by a colossal rented pandal—a red-and-blue-striped rectangular tent that accommodated 20,000 people. Within, tables stretched along the left side, where guests received free halavah and puris each evening. On the right side, the devotees set up a question-and-answer booth and book tables with Prabhupada’s books, ancient yogic texts that he'd translated and commented on. At the far end stood a stage where 40 western devotees sang, danced and worshiped brass Deities of Radha and Krishna on a central altar. To the left of the altar was a slightly raised seat with a throne-like back for Prabhupada.

The expansive area in front of the stage and extending to the back of the pandal was for guests, and each evening for 11 days, beginning on March 25th, 1971, 15,000 people poured in to sit on one of the many chairs (for VIPs and the handicapped) or, more likely, on one of dozens of immense, thick, red-and-blue-patterned cotton dhurries that covered the ground.

The crowd’s attention was riveted on the young, zealous Americans and Europeans who had brazenly adopted their culture and were playing two-headed drums and small hand cymbals and boisterously singing in Sanskrit while dancing to the beat.

There was hardly a westerner in the audience. I sat on the stage with my fellow Caucasians, feeling awkward and hypocritical. I was not a believer, not a follower, not even a supporter of the devotees. But the devotees didn't mind my presence, and the stage gave me a good view of the audience. As the western devotees mesmerized the multitudes in front of them, the multitudes mesmerized me. This ocean of people was as spellbound by the devotees as children are while watching a deft magician. And they sat for hours, utterly enchanted. Their reverence had an honesty and innocence and power I'd never before experienced. I didn’t know what to make of it.

The eccentricities of the devotees in the Brooklyn asrama, the cold and austere London asrama, the airy Akash Ganga asrama and my brief unbelieving dip into the Krishna doctrine had in no way prepared me for this event. The personalities and backgrounds of the western Hare Krishna devotees in India made them an odd group, but whatever they didn't have in common with one another—which was a lot—they made up for with their audacious, total endorsement of Prabhupada and his mission. Their enthusiasm exuded on the pandal stage, springing forth in song and vivacity, and making what seemed to me like an indelible impression on the droves who sat before them.

After some time, Prabhupada arrived, climbed the six steps onto the stage, came before the Deities of Radha and Krishna, and offered his prostrated obeisance. He then rose, folded his hands in reverence before the Deities, walked a few steps to the raised dais to the left of the Deities that was meant for him, set aside his cane, and climbed onto the dais to sit cross-legged before the huge crowd. He was the only Indian on stage. One of his disciples led a song-prayer, and Prabhupada and the other devotees sang responsively while a priest performed an evening Deity ceremony. When the blowing of the conch signaled the ceremony’s end, the devotees bowed down, their foreheads touching the stage floor. Prabhupada recited lengthy Sanskrit prayers, his voice sonorous over the many loudspeakers stationed throughout the pandal. Then he began to play his small, shiny, brass hand cymbals in a steady one-two-three beat—ching, ching, sizzle. He closed his eyes and sang:

Jaya radha madhava kunja bihari

I could not place his voice. It was neither western nor eastern nor anything in between. Its refined baritone strains were resonant with emotion. The devotees around me, two of them playing drums in time to the singing, and several more playing small hand cymbals like Prabhupada's, responded by singing the same words. Prabhupada listened to their singing and then sang the next line:

Gopi jana vallabha giri vara-dhari

Again the devotees responded. The vast audience was still and silent.

Jasoda-nandana, braja jana ranjana

Prabhupada’s voice had a penetrating sincerity, and the devotees offered his words back to him.

Jamuna-tira-vana-cari

Once the devotees had responded, Prabhupada began the lines over, picking up the beat. I vaguely remembered that I had heard this short song in the Brooklyn temple, but it hadn't impacted me then. Now it sounded Elysian.

Prabhupada deepened his concentration and increased the tempo as he sang the same lines a third, fourth, and fifth time. He suddenly stopped, opened his eyes, put his cymbals aside and leaned into the microphone, his brow wrinkled with earnestness. Again he recited prayers while the devotees bowed in supplication.

The devotees sat attentively as Prabhupada cleared his throat and began to speak, “Ladies and gentlemen, thank you very much for taking so much trouble to participate with us in this great movement of Krishna consciousness. As I am repeatedly placing before you with all humbleness that this movement is very, very much essential, not only at the present moment, but also all the time.”

My skepticism bristled. “Of course he's going to say the movement he started is essential,” I thought. “Don't all leaders think what they're doing is essential?”

Prabhupada continued, explaining that this is the age of disagreements and quarrel. Everyone has their own opinion and is prepared to fight with others. So putting forth different theories can't solve the world’s problems, he said, because there have always been different philosophers and different scriptures.

He said, "So simply by argument and reasoning you cannot make spiritual advancement. You may be a very good logician, putting forward nice arguments, but somebody may come who is better than you. He will spoil all your logic and he will establish his own logic. Therefore you cannot understand the Absolute Truth by argument, by material dealings.”

As he spoke, my mind drifted to the exotic circumstances in which I now found myself—sitting on a raised platform in the hub of India’s most cosmopolitan city before thousands who were eagerly hearing from a slight, well-spoken guru. I missed what he said next, but perked up when he spoke of Malati’s three-year-old daughter Sarasvati, who had charmed the audience earlier with her dancing and singing.

“You'll be surprised...” Prabhupada continued, “...this little girl, the other day we were walking in Hanging Gardens, and this little girl, as soon as she saw some flower, immediately she expressed her opinion that these flowers should be taken and made into a garland for Krishna. This is Krishna consciousness. She is being taught from the very beginning of her life how to become Krishna conscious. So it is not difficult. It depends only on the training. Even in this old age, and especially in this age, this method is very simple. Simply we have to agree to accept it. That’s all. Krishna consciousness is the simplest form of self-realization and advancement in spiritual life.”

Sarasvati was a sweet girl who usually seemed happy, despite living in such a foreign place. “But...” I thought, “...was she being trained or indoctrinated? When she came of age, would she continue to think that flowers were meant to be used for God's garland? Or would that idea, and so many others that Prabhupada promoted, become irrelevant to her and forgotten?” I felt alienated from the devotees, who themselves were aliens.

As Prabhupada left at the close of the program, a swarm of admirers from the audience engulfed him, scrambling to touch his feet. Devotees encircled Prabhupada, trying to hold back the crowd’s swell. The fervid pushing, jockeying, and tussling was reminiscent of Beatlemania. Prabhupada had spoken with urgency and intensity, but in a measured and logical way, yet he'd evoked frenzy. I stood to the side, watching and wondering and distanced. India was so often a soup of showy reverence, I didn't take this display too seriously.